My godmother, Mary Sommerhauser Russell, chose to serve in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps during WWII because she was tired of wearing white nylons. Nurses back then, much in demand, had a choice as to which service they could join.

“I had good looking legs and wanted to show them off. I liked the Army uniform better.”

While she admits it sounds vain, she has no regrets because, with the army, she saw real action. Mary landed on Omaha Beach in August 1944, two days after the Liberation of Paris. She was 22 years old.

She tells of sailing on the RMS Queen Mary, which had already been whisked to Sydney, Australia, to be converted into a troopship, painted navy gray, stripped of its finery and had degaussing coils added to protect the ship from magnetic mines.

For her journey to Europe the approximately 72 nurses were sequestered on the upper deck with the thousands of male troops below.

“I had a date every 15 minutes,” she smiles slyly. “But then in the middle of the night they came and made us move to a lower deck.”

Well, that got Mary’s goat. She rose early the next morning to see who had taken her precious upper deck and when she looked up, there, standing at the railing, was a well-known world leader dressed in his famous blue jumpsuit, holding his cigar. Winston Churchill traveled frequently as “Colonel Warden” on the Queen Mary, who, because of her speed, was difficult for any U-Boat to catch, and became known as the “Gray Ghost.”

Raised in Butte Montana, in a German and Irish household, Mary knew how to get a job done.

“When we got there they kept telling us we would have a hospital, but we worked in tents in the fields. To save our precious penicillin we would dig holes in the cold ground, put the vial of penicillin in a condom, then in a can and bury it. There was no refrigeration. You made due.”

She talks of how the snow covered soldiers arrived at their medic tents with disfiguring frostbite, the engineers that stayed with the makeshift hospitals to keep the equipment running, the death and hope they all lived with daily.

There is no telling how many lives she touched in an attempt to save our boys and the horror she keeps privately tucked away.

But I know that from now on I will refer to First Lieutenant Mary Sommerhauser, Mrs. Ralph Russell, who just turned 95, as the real Queen Mary–for all the love and support she gave to the hundreds of troops on the ground in the European Theater. I am so proud she is my godmother.

On Friday, August 10, 1945, Emperor Hirohito urged Japan’s War Council to submit a formal declaration of surrender through ambassadors to the Allies. Even though Japan’s war causalities had been great, most of their fleet destroyed and their people were starving, it took a second atomic bomb, dropped on Nagasaki, three days after Hiroshima, for Japan to finally make the decision to surrender. However, the surrender was not formally announced to the land of the Rising Sun until August 14, 1945. And over that four day time period, east of Okinawa, a Japanese submarine sank the U.S. landing ship, the Oak Hill, and a destroyer the Thomas F. Nickel.

On Friday, August 10, 1945, Emperor Hirohito urged Japan’s War Council to submit a formal declaration of surrender through ambassadors to the Allies. Even though Japan’s war causalities had been great, most of their fleet destroyed and their people were starving, it took a second atomic bomb, dropped on Nagasaki, three days after Hiroshima, for Japan to finally make the decision to surrender. However, the surrender was not formally announced to the land of the Rising Sun until August 14, 1945. And over that four day time period, east of Okinawa, a Japanese submarine sank the U.S. landing ship, the Oak Hill, and a destroyer the Thomas F. Nickel. However, it did not stop General Anami, the member of the War Council greatly opposed to the surrender, from committing seppuku, a warrior’s suicide ritual.

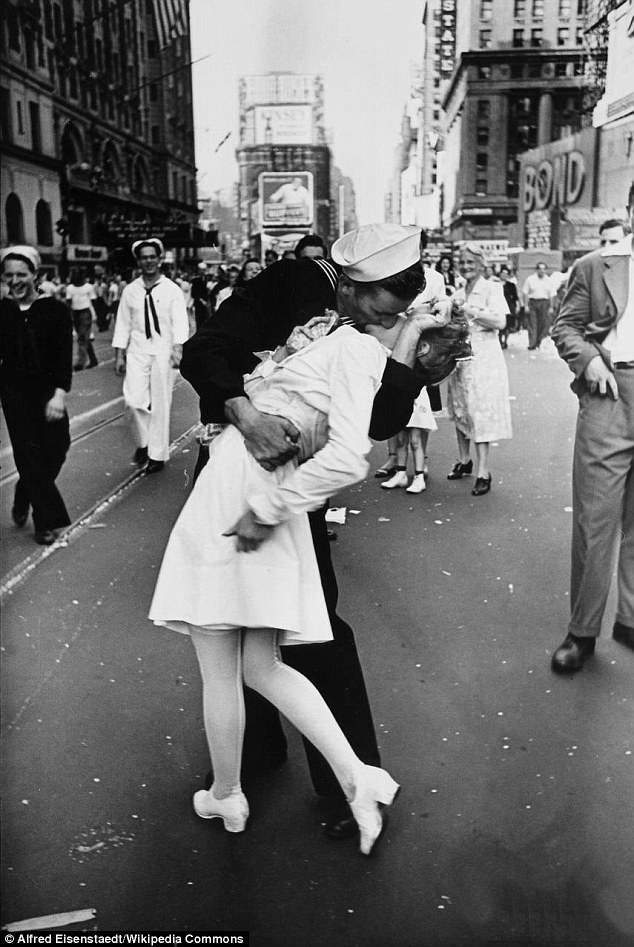

However, it did not stop General Anami, the member of the War Council greatly opposed to the surrender, from committing seppuku, a warrior’s suicide ritual. Alfred Eisenstaedt’s iconic photo for Life Magazine of a sailor kissing a nurse in New York’s Time Square captured the overwhelming sense of relief and joy of the Allied nations emerging from the turbulent years of a long and bloody war.

Alfred Eisenstaedt’s iconic photo for Life Magazine of a sailor kissing a nurse in New York’s Time Square captured the overwhelming sense of relief and joy of the Allied nations emerging from the turbulent years of a long and bloody war. His wife Ginny was a freshmen and student librarian in college, yet had no idea of the location. She remembers that soon after the attack and war was declared, there were very few men left in any classes, until the Air Corps Cadets arrived.

His wife Ginny was a freshmen and student librarian in college, yet had no idea of the location. She remembers that soon after the attack and war was declared, there were very few men left in any classes, until the Air Corps Cadets arrived..jpg?resize=354%2C283)